Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Dream Project Adopts Transmedia Strategy

-MfC Staff Writer

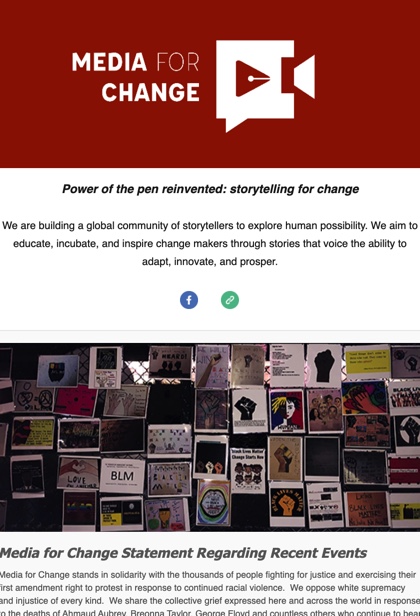

In 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic was sweeping through the United States and the world, Media for Change launched the Dream Project by asking people to submit short videos via the Gather Voices app. In the selfie style videos, people from near and far shared their dreams for a post-COVID 19 world.

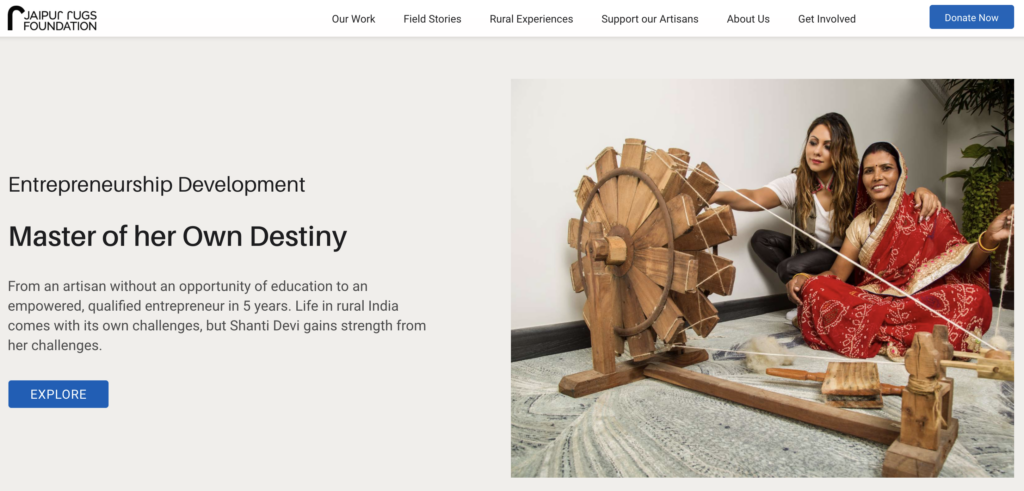

Based on the idea that it is necessary to visualize the world before seeking to make a difference, this work has continued and in 2021 Media for Change launched the podcast Where Dreams Come From. The podcast features deep conversations with people around the world who credit their dreams as drivers for personal success in life. Planned as a multilingual series, the podcast is now releasing episodes for season 1 in English. Episodes in German are expected for release soon, with other languages to follow.

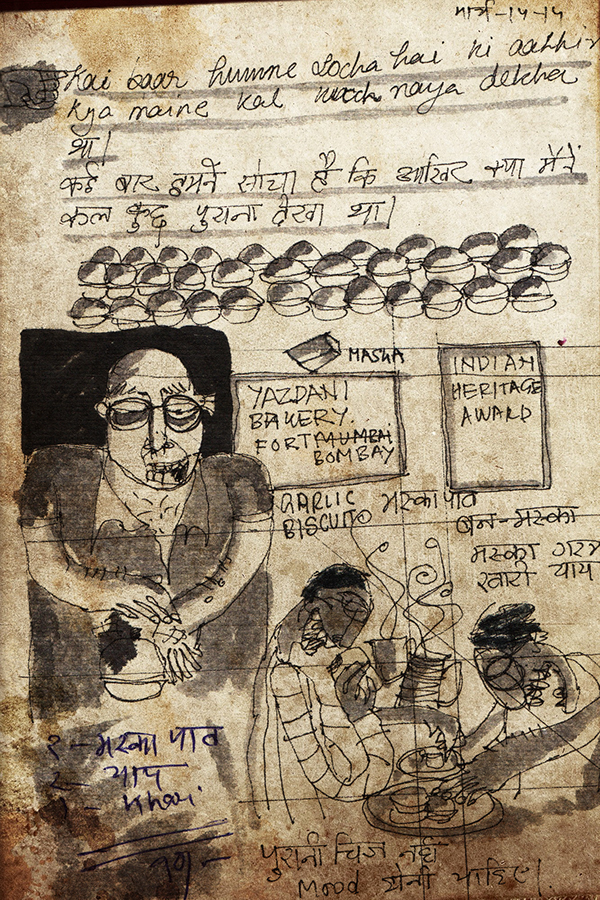

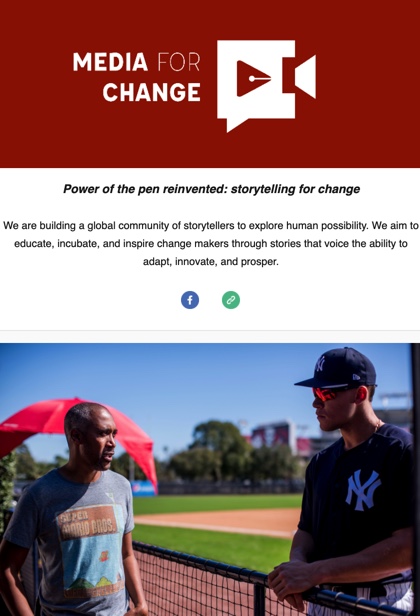

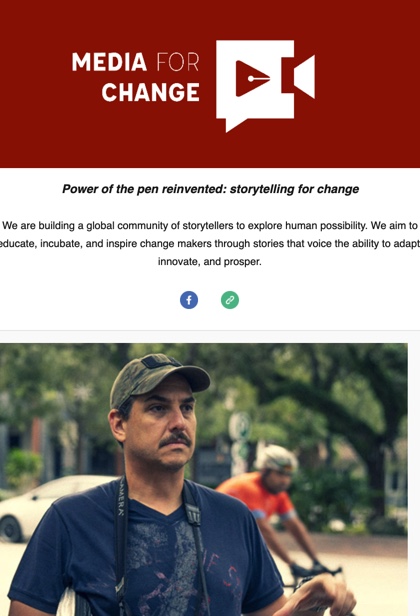

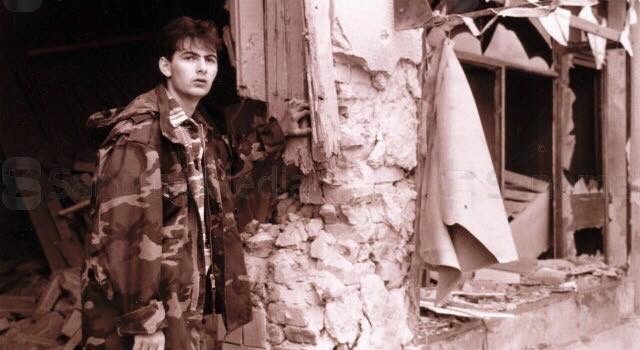

Media for Change founder Sanjeev Chatterjee, inspired by a positive change one of his former students was making in life, traveled to meet up with him in Hawaii. Chatterjee first met Tvrtko Vujity (pronounced: taVartko Vooich) as a graduate student in the journalism program at the School of Communication, University of Miami in the mid 1990s where Chatterjee is a professor. Since then, Tvrtko has been chasing his childhood dream of becoming a journalist. He was studying journalism at the University of Miami on a Voice of America scholarship after winning the Pulitzer Memorial Medal (not to be confused with the American Pulitzer Prize) for his reporting of the Yugoslav War. Although Tvrtko never took a class with Chatterjee, they became close as Chatterjee was making a documentary film From the Shadow of History about peacekeeping in the former Yugoslavia at that time.

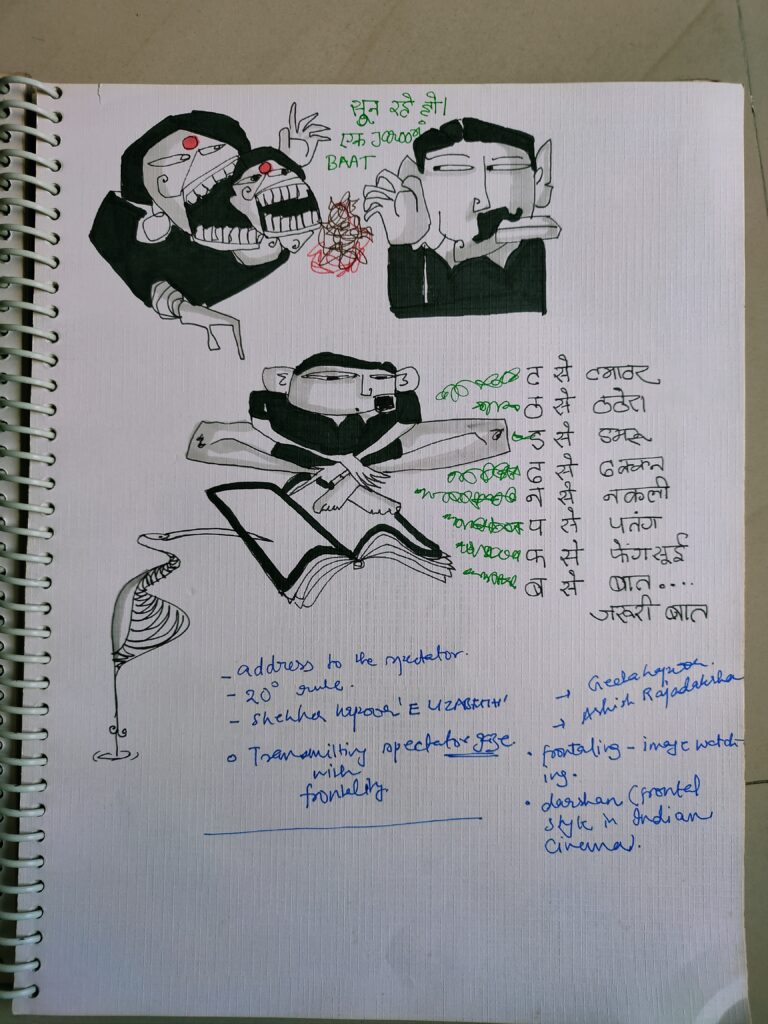

After returning home to his native Hungary from Miami, Tvrtko went on to become a celebrated journalist not only in his country but also in neighboring Slavic language regions including Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia and other countries. His primetime TV show Napló (diaries) became widely recognized. He brought back the last Hungarian POW of WWII who was languishing in a mental asylum in remote Tartarstan, he snuck into North Korea as an aid worker, he reported on the genocide in Rwanda, he reported from the nuclear disaster site at Chernobyl – there are endless stories over a period spanning more than 2 decades.

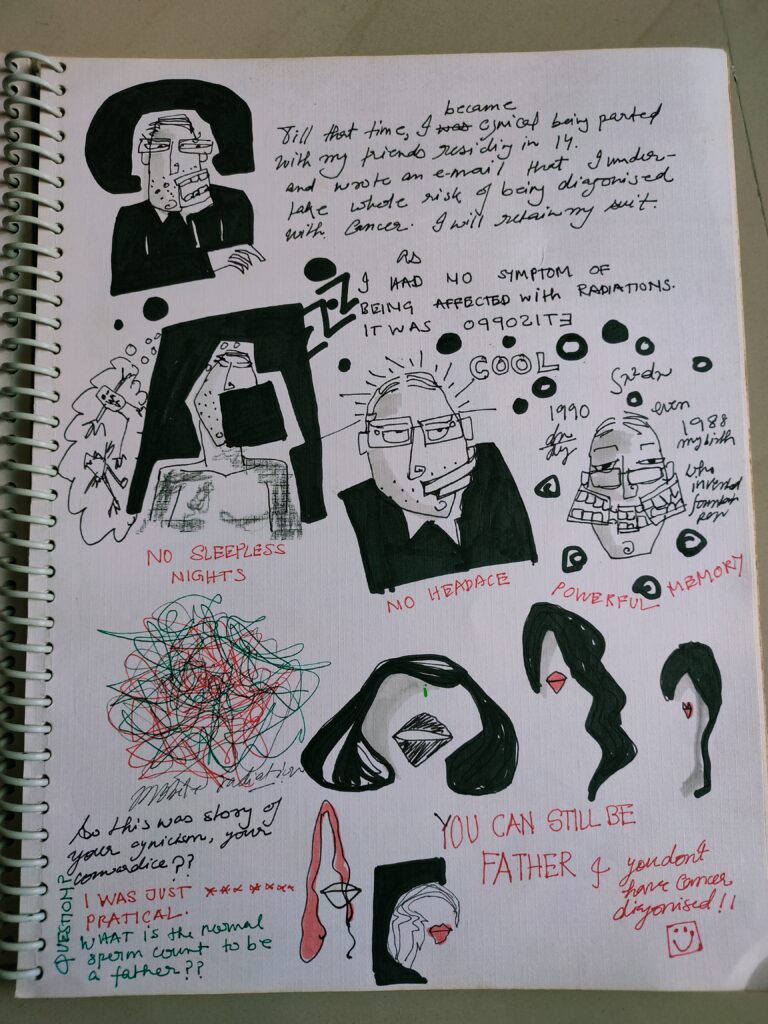

“I was eager to meet Tvrtko after all these years because he was making a big change in his life’s trajectory. He told me he had been telling the stories of hell on earth, but now he wanted to discover paradise” said Chatterjee. Apart from his television show, Tvrtko has written 13 books titled Pokoli Történtek (Stories from Hell). His very successful public talk series Tvrtko Across Borders addresses his learnings from his work. However, after revisiting Chernobyl in 2019, Tvrtko experienced a reckoning. He no longer wanted to relate stories from hell. A combination of intent and circumstances led to Tvrtko moving to Hawaii with his family. He says he is living the aloha life. Still seeking to fulfill a dream in this life.

For Chatterjee, the turn in Tvrtko’s intentions is just a plot twist in the story. “This is potentially a story about reinvention, an evolution in the story of Tvrtko’s dream of becoming a journalist. This could be a great story” said Chatterjee. Media for Change is now in preproduction of a documentary project about Tvrtko’s journey thus far and into the future.

The term transmedia was coined by Henry Jenkins who currently serves as the Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism, Cinematic Arts and Communication at the Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California. The term is used as an adjective to define a certain kind of journalism, filmmaking, game design, storytelling…that uses multiple platforms to reach diverse audiences through diverse stories to convey the same message. In this case, the message is about the importance of dreaming about and visualizing a world we want to live and thrive in.