Daniella Zalcman

Bridging the gap between art and journalism

Daniella Zalcman uses the power of the lens to redefine storytelling around the world

BY Isabella Vaccaro

Daniella Zalcman is a photographer. She’s also a journalist. And a champion for equal rights. Zalcman uses a technique called double exposure photography to tell stories. And she began a non-profit organization for women and non-binary photographers. And yet, some still believe Zalcman’s images aren’t journalism, but merely art. Here’s why they’re wrong.

In college, Zalcman became interested in how western colonization affects other parts of the world, and, in 2013, found herself in Uganda documenting the rise of an anti-gay law, though she’d originally planned to cover the independence of South Sudan.

“I actually sort of accidentally ended up on that story,” said Zalcman. “I ended up in Uganda waiting for my visa to come through. And I was just sort of looking for a story to work on. And I happened to be [there] shortly after the first gay rights activist was murdered.”

Zalcman said she became close with the small activist community in Uganda and started reading up on what she described as an “insane anti-gay law,” which, according to her website, criminalized acts of homosexuality and threatened sentences as long as life for these ‘crimes.’ But for Zalcman, one thing stood out as even more shocking than the law itself.

Noise coming from western media accused Uganda and the bill as being ‘backwards,’ but in 2013, the United States had not yet even legalized gay marriage. Zalcman wondered what right western media outlets had to scorn other cultures when our own wasn’t as progressive as we thought? Perhaps western media was simply projecting a truth they knew to be a fault none other than their own.

“The origins of homophobia in East Africa are very clearly connected to British imperial rule and to American evangelicals,” said Zalcman. “And so, you know, hearing about that story without hearing that context seems like a huge disservice and sort of a grave misstep in journalism to me.”

Zalcman said this project opened her eyes not only to the effects of western colonization on other countries, but also to the possibility that journalism and how we tell stories needed a makeover.

“I think there are huge structural problems with journalism,” said Zalcman. “It has largely been an institution that is deeply colonial and that is predicated on this idea that we in the West are more equipped and more able to tell the stories of people around the world than they are themselves, which is categorically untrue.”

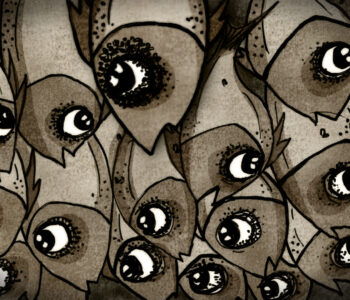

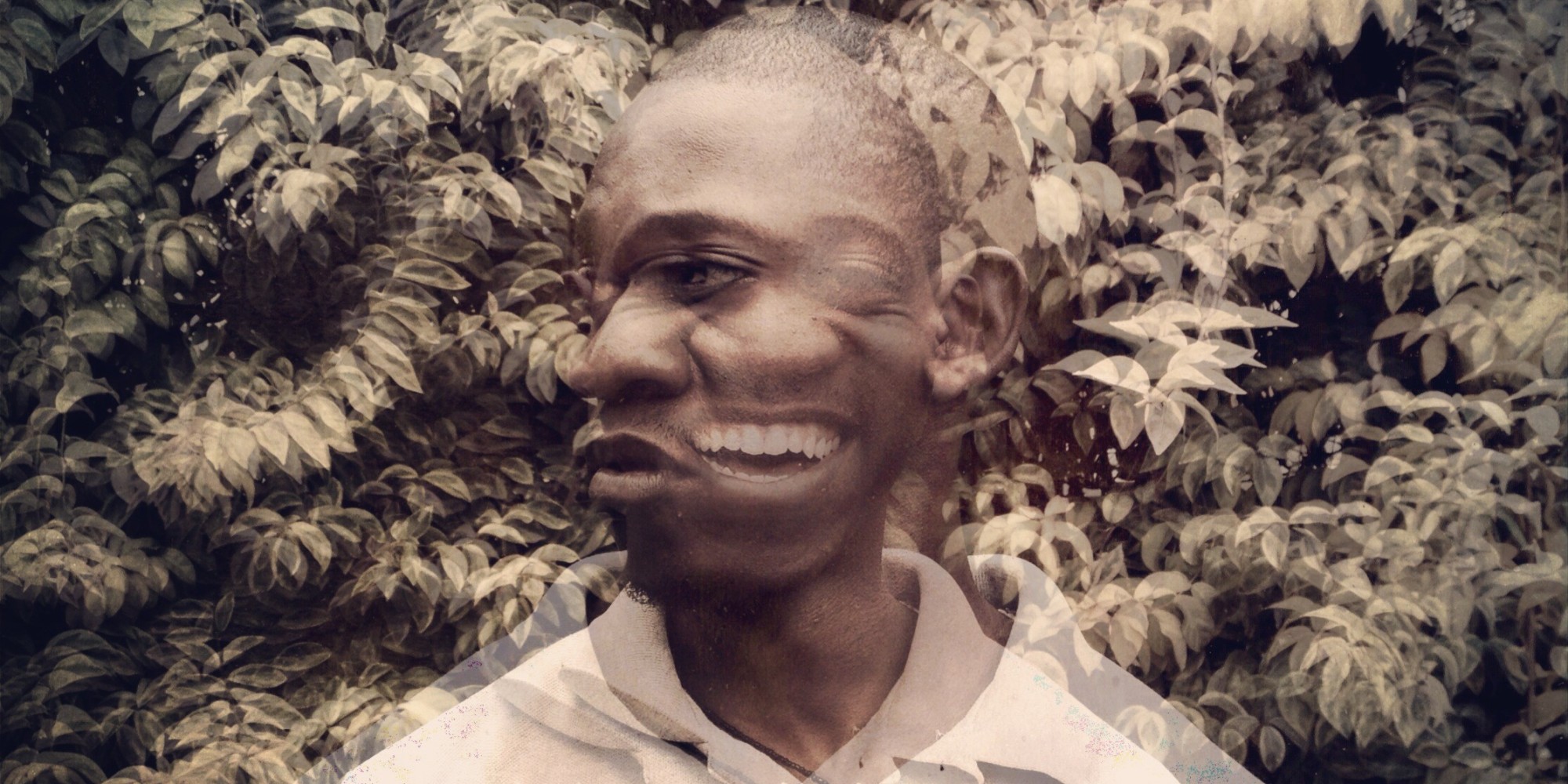

Zalcman began brainstorming new ways to tell stories and found a photographic technique called multiple exposure, which basically means overlaying multiple images at different opacities. Not only did she use this technique in Uganda, but also to portray both the faces and experiences of the subjects of her next project, called Signs of Your Identity.

Signs of Your Identity focused on survivors of a Canadian government initiative started in the 1870s, which forced indigenous children out of their homes and into boarding schools where they were beaten, sexually assaulted and stripped of their indigenous identities.

“I was fundamentally trying to tell a story that was rooted in memory and was dealing with these ideas of intergenerational trauma, the things that we pass from generation to generation and it was such a complicated story to tell, visually,” said Zalcman. “I ended up creating these double exposure portraits that overlaid the images of boarding school survivors, with the physical sights and memories of their boarding school experiences.”

Though visually chilling, Zalcman said, initially, her photos were brushed off by the editors she sent them to. “This is nice, but it’s not journalism,” is the response she’d get. But after a few years, and as the media landscape changed quickly into an increasingly visual place, the industry began to change their tune about Zalcman’s work.

“I am first and foremost a journalist,” said Zalcman. “But, I also believe that my work is art, and I believe that most powerful meaningful photojournalism is art. But for me, the question is really ‘am I working as a storyteller with transparency and honesty and integrity?’ And as long as that is the case, as long as I’m being upfront about my process and the story that I am trying to tell and I’m treating the people whose stories I’ve tried to tell with respect and dignity, then that’s all that matters.”

Zalcman hopes students of all ages can learn something from her work, especially in working with alternative storytelling formats, because storytelling, as she puts it, is “the fabric of human life.”